A man born with Usher syndrome type 1b, a rare genetic disease that causes congenital deafness and progressive blindness, has reportedly experienced “substantial improvement” in his vision, after receiving a new type of gene therapy as part of an ongoing clinical trial.

The rest of this article is behind a paywall. Please sign in or subscribe to access the full content.The 38-year-old man was the first patient in the world to be given the new treatment, and a year later, he stands as the first evidence that it can work – and how life-changing that could be.

“Now I can recognize faces, see the warehouse aisles at work, and read subtitles on TV. It’s not just about seeing better – it's about starting to live again,” said the patient in a statement.

Usher syndrome is caused by mutations in a gene called MYO7A, which provides the instructions to produce a protein that plays a critical role in the inner ear and the retina, which converts light into electrical signals that our brain decodes as images.

The mutations in MYO7A mean that people with this condition are typically born with severe to total hearing loss, and progressive vision loss that usually begins as a teenager or in young adulthood.

Gene therapy for such conditions is a rapidly expanding field, but when it comes to Usher syndrome type 1b, there’s a problem – MYO7A is a big gene. Too big, in fact, to be carried by the viral vectors that are typically used to deliver healthy copies of a gene to cells in existing therapies.

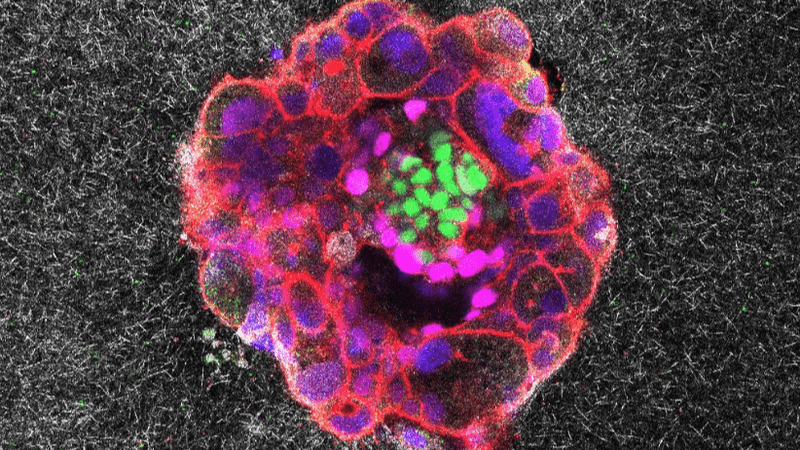

So, researchers at the Telethon Institute of Genetics and Medicine (TIGEM) in Pozzuoli, Italy, came up with a possible solution: split the gene in half. Instead of just one vector, the gene is spread over two. Once delivered, cells in the retina can reassemble the two halves and use them to produce a fully functional copy of the protein MYO7A encodes.

In theory, this should lead to restoration of vision. The initial findings from the trial, which has so far involved eight patients, suggest that seems to be the case in practice – and quickly, too.

“In the first patient treated, improvements were evident just two weeks after the procedure and continued over time,” said Professor Francesca Simonelli, head of the Center for Advanced Ocular Therapies at Vanvitelli University, one of the centers taking part in the trial. These improvements were in both near and distant vision, and even when there was little light.

But it’s not just about whether a treatment works – it needs to be safe as well. Again, that appears to be the case here, with no serious adverse events reported, and the side effects that did arise being only mild, infrequent, and easily managed.

Still, it’s important to emphasize that these are preliminary findings, with the trial set to continue over the coming months by testing out a higher dose of the treatment in a further seven patients. Even if all goes well, there’s still a long road ahead before the therapy could be approved – but the researchers are feeling positive.

“This is still an ongoing trial, but the signals observed so far offer new hope for other inherited eye diseases that currently have no treatment options,” Simonelli concluded.