When it comes to the human memory, many mysteries remain, but a new study is helping to solve some of them by peering into the brain’s “filing cabinet”. Using recordings of brain activity and machine learning tools, a research team has revealed new insights into how our brains sort and catalog memories of objects.

The rest of this article is behind a paywall. Please sign in or subscribe to access the full content.For any Gen Zers in the audience, a filing cabinet is an archaic piece of office furniture that was used by your ancestors in the dim and distant past for storing bits of paper. According to the study authors, this pre-digital relic is also a handy metaphor for how the brain holds on to visual memories of different objects.

While there’s a lot we don’t understand about memory, one thing we’re reasonably certain of is that the hippocampus plays a very important role. It’s vital for our ability to remember the “where” and “when” of things, but it’s simply not feasible for it to store an individual memory of every single object we encounter as we go about our lives. Therefore, neuroscientists reasoned, the hippocampus must be making use of some kind of categorization system.

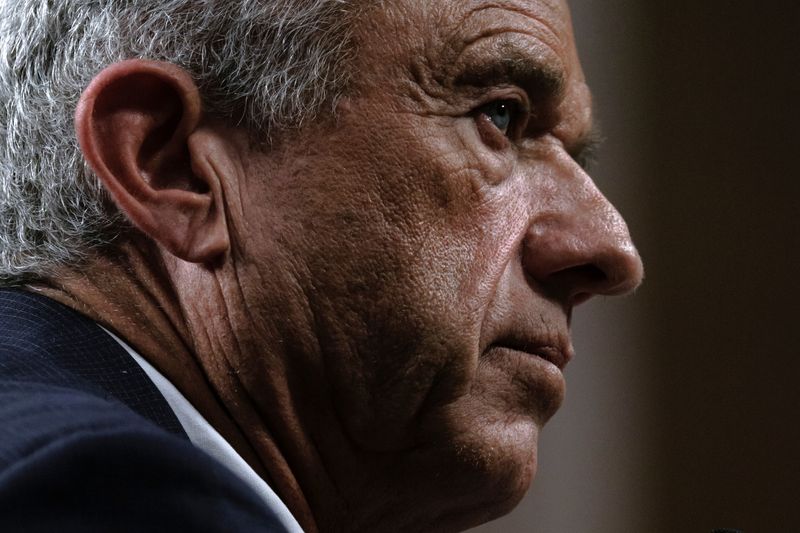

“[I] wanted to take the opportunity to answer some fundamental neuroscience questions. And this is one of them,” explained senior author Dong Song, an associate professor at the University of Southern California (USC), in a statement.

Song and the team recruited 24 patients with epilepsy who already had electrodes implanted in their brains to help doctors pinpoint the location of their seizures. This makes this patient group uniquely well-placed to help with scientific investigations alongside their own medical treatments. Many of these patients also experience memory disorders themselves, so they can benefit directly from this type of research.

While the participants completed a memory recall task, the team were able to record spikes of activity from two populations of hippocampal neurons using the electrodes they already had in situ.

“We let the patients see five categories of images: ‘animal,’ ‘plant,’ ‘building,’ ‘vehicle,’ and ‘small tools.’ Then we recorded the hippocampal signal,” said Song. “Then, based on the signal, we asked ourselves a question, using our machine learning technique. Can we decode what category image they are recalling purely based on their brain signal?”

In other words, could they “read the patients’ minds” by figuring out, just from their brain recordings, what type of image they were remembering at a given moment?

It turns out that yes, they could.

“We can pretty accurately decode what kind of category of image the patient was trying to remember,” said Song. This confirms that the brain does sort objects into categories, as had long been suspected.

“With this knowledge, we can begin to develop clinical tools to restore memory loss and improve lives, including memory prostheses and other neurorestorative strategies,” added study co-lead Charles Liu, a professor of bioengineering and director of the USC Neurorestoration Center at Keck School of Medicine.

As for the next steps, one would be to expand this work beyond the five categories they covered, especially because in our everyday lives we encounter various objects that could straddle multiple categories – it will be interesting to see how the brain deals with these. The team also suggested that future research could try and capture a more real-world setting, as well as explore longer-term memory storage. Once objects are filed away, do they stay there or does the system evolve over time?

To be fair, we did say right up top that there are still a lot of memory mysteries left to uncover.

The study is published in the journal Advanced Science.